Kevin Thomas is a Carpenter and restorer of 1980s desert bikes. For the third issue of Getting into Adventure I went over to see him at his workshop to find out more about the increasing demand for the latter…

“I started like most people; my dad getting me into bikes, sitting me on the handlebars and taking me out for a ride. I never had much money as a kid but always worked on and built bikes with my dad and then on my own. There was an old Bantam sat in an old boy’s garage down the street, and every time I rode past on my pushbike I asked if it was for sale. It was two years until the old boy asked if I wanted to buy it. And that’s where it all began.

At the age of 17 I passed my test in the January, bought a 250 LC and was in Le Mans in March for the 24 hour race. It just went from there, and by the time I was 21 I’d done a three month tour of Europe, finding myself in Algeciras and realising Africa was just across the water.

Having crossed into Morocco I then entered Algeria, before riding all the way down to Niger, where I met two Germans riding Honda XL600 XMs. I came back from that trip and from there really got into the idea of doing a rally. I started racing enduro bikes, got fitter and learned the art of navigation. I had a 660 Tenere and raced rallies in Africa. I just took to it like a duck to water, absolutely loved it, and from there came my passion for working and restoring the desert race inspired bikes of the 1980s.

I just love the style of that era of bikes. They’re practical and functional. I generally prefer the Yamahas to work on for the fact that a lot of parts crossover between models. To fit a water-cooled engine in an air-cooled frame is just a case of nuts and bolts. The gearboxes are no longer available for the earlier bikes but you can fit a later gearbox cluster straight in. You can’t do that on modern bikes so easy, not with complicated CAN-bus systems and the numerous electrical components.

“The issue is increasingly finding the bikes to begin with”

The issue increasingly is in finding the bikes to begin with. The numbers are drying up, mainly because people are wanting the bikes they couldn’t afford when they were young or had when they were young and regretted selling, but there are only so many of them out there and the supply is just starting to dwindle a little bit. A few years ago the Italians realised they were selling all their own bikes to us and now they’ve gone down the same route, so the nostalgia thing has kicked in over there too. Those that have got them are starting to hang on to the them, whilst those that fell by the wayside are just parts on eBay. That’s good for repairing existing bikes, but not so good for the stock of complete bikes to own and restore.

I find most people interested in this type of bike are 40-50 year olds, with a growing number of young riders who never saw this era of bike, but who are now seeing them and interested in what they have to offer. It’s old school but it’s still practical and its still usable. Price wise it’s also affordable. I’ve just done a restoration on a XT600 that the guy paid £800 for. Another £1700 for the restoration and he’s got himself a good solid bike that’ll last him a long time. Most people come to me with a bike they already own, though I can source a bike for people, they just could be waiting a long time for the right bike to come along.

Believe it or not but plastics are becoming the biggest issue. Yamaha has no stock of new plastics anywhere, so it’s a case of sourcing them where you can, but it can be difficult. The Australians have started making some moulds to make them in glass fibre. The Germans are working on some injection mouldings. So there might start to be more parts coming through as the restoration of this era of bikes becomes more popular, and commercially viable.

Before starting on the restoration of a bike I like to talk to owners about what they’re after, what they intend to use it for, what their interests are, perhaps where their history goes back to in motorcycling. Sometimes it’s doing exactly what the client wants, and that’s pleasing when you get it right, and then there’s the open brief where you do whatever you want with it. When that happens I tend to build a bike that I would like for myself but haven’t got the time or money to build, but can do so for someone else. Once I’ve built a bike for someone then I’ll love it like my own. I built one bike for a guy and every year he gets me to service it. We go out for a ride and I get to see ‘my’ bike again. It’s not my bike, but I created it. It’s the same bond I have with some of the furniture I make. The carpentry and the motorcycling compliment each other very well, especially in the winter when I like to focus on the bikes.

Most of all I like to see my bikes being used. I really dislike the classics being tucked away in garages and used as show-pieces. These bikes are all built to be used. It’s what they were made for. It’s really sad to see them not being ridden. That shapes my approach with the bikes. Aesthetics are important but it’s more about the mechanics of the bike.

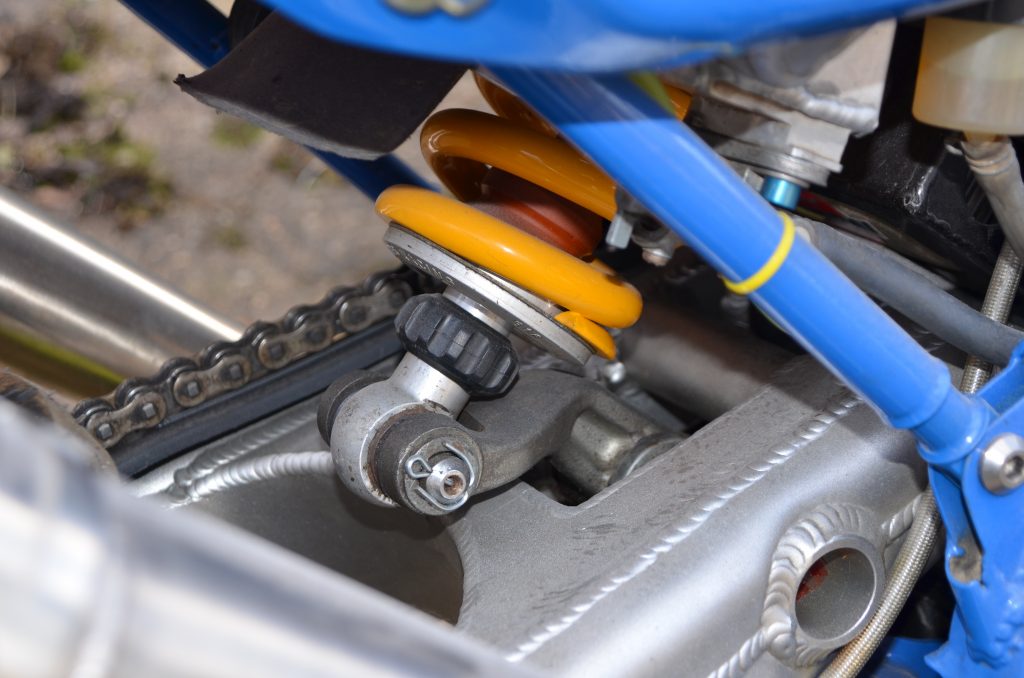

All the bikes are renovated with top notch suspension, not necessarily the most expensive but the best I can get for the bikes. Front forks are stripped, re-shimmed and rebuilt for purpose, same with the rear shock. They all need to work properly. That doesn’t mean to say you can’t make it look pretty, but the mechanicals have to be right first.

I find it’s quite an exciting process, almost like a blank canvas, and it’s really satisfying when a customer turns up to collect their bikes. They fire it up just like they would a new bike and away they go. You teach them a few basics for oil changes as it’s a dry sump, and that’s it, the beginning of their own classic adventure.”

You can find out more and get in contact with Kevin at www.woodcutterbikes.co.uk

Meanwhile, Kevin’s Top Five tips when buying a classic desert bike:

- Don’t worry about the mechanics, worry about the cosmetics in terms of what you’re buying, because the mechanics can always be fixed, but the cosmetics are getting harder to come by, and cost more. If you get a bike that looks tidy but is mechanically tatty then you’re better off than the other way around.

- Wheels are always fixable so don’t worry about those. You can always rebuild them or use items from another bike.

- Buying a bike you have some emotional bond with is always good, as you’re more likely to see a project through to the end.

- Do a bit of research in advance to see what kind of parts are available, and what kind of price they are. There are some bikes out there that are easy to get the bikes, but hard to get the parts.

- Join a club. There’s a lot of knowledge and people who are passionate about that mark can help you out with searching or locating parts.

A few more photos…