Almost 16000 miles in and the Himalayan has surpassed expectation as a travel bike. Here are my thoughts on this single cylinder, £4000 machine…

I bought the Himalayan without riding it. I was laid up with a broken ankle over winter and wanted what I hoped would be a solid bike for leading the semi-guided ‘Garbage Run’ tours I had lined up in 2018; three from Land’s End to John o’Groats, one around Wales, another around Devon and Cornwall and the big one across America, leading a group of 11 riders from New York to Los Angeles.

The Himalayan hadn’t received great feedback from its early launch in India. Quite a few owners had complained about reliability issues and there was plenty of internet chatter about it being a flawed machine. It was two years after the launch in India that it was finally released in the UK. We would get it with what promised to be all of the initial issues ironed out, plus electronic fuel injection and ABS. Early forecasts of it costing £3999 seemed too good to be true. It looked to be a bit of marketing bluster to get people interested before pumping up the price to nearer £5000 when it finally did hit the dealerships. When it actually did arrive at £4000, plus £200 on the road costs, I was intrigued. I thought for the price you don’t really have a lot to lose, and I liked it’s under-dog status. The forums were full of people saying it was going to be a lousy machine, but somehow that made it more appealing and I just had a good feeling about the bike. So I bought one, and over the following 8 months put 16,000 miles on it. Here’s what I found.

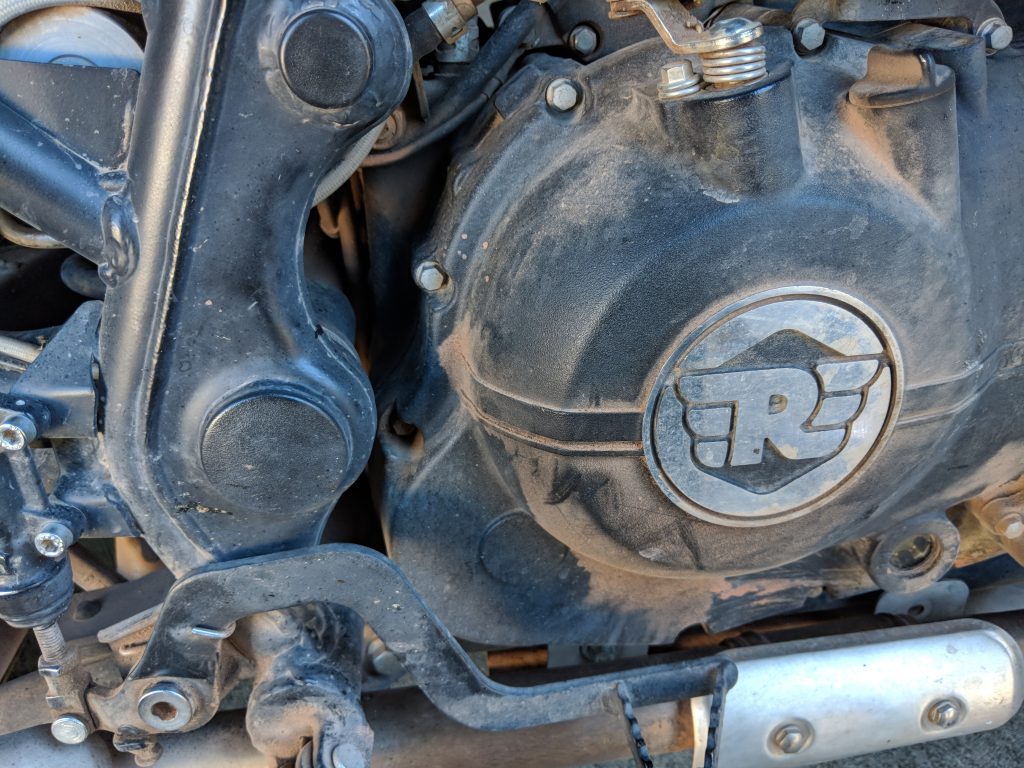

ENGINE

People wrote off the bike for it ‘only’ having 24.5bhp. From a single-cylinder air-cooled 411cc engine this didn’t seem a great deal, but I’d not long since ridden the Suzuki V-Strom 250 and Honda CRF250 Rally for a Bennetts Bike Social group test – both bikes making similar power as the Himalayan – and I was actually surprised that in the real world they were actually plenty powerful to keep up with modern traffic flow, with both bikes never feeling particularly slow, or dangerous, even on the motorway. And so the power output of the Himalayan didn’t put me off from the get-go.

And the engine is ‘long-stroke’ in that the stroke is longer than the bore, meaning that it doesn’t rev as high as most other bikes, but it does generate a decent amount of torque, or ‘thump’ as you might call it, especially at lower revs. Torque is a healthy 32Nm and to be honest it is a far more refined and modern engine than I was expecting. I’d ridden a classic Bullet 500 and quite liked it’s vintage nature and expected the all-new single overhead cam engine in the Himalayan to have similar level of gruffness and vibrations. But it’s not like that. It’s very smooth off the throttle, the fuelling (by Keihin) is excellent and the engine’s balancer shaft means that there’s barely any vibrations through the bike at high revs. It definitely feels and performs like a modern engine, just one that clearly has a different characteristic to what we’re used to.

It’s not a fast bike. If you get on it and want to thrash it to the 6500rpm red line then it doesn’t really respond in the way a CRF250L might, a bike that does like to rev, or the BMW G310GS which again only really comes into its own at the last third of the rev range. Instead, the Himalayan is all about mid-range torque and short-shifting through the gears, allowing the bike to generate power at its own pace and once you get into the rhythm of the bike it seems to deliver more fire than you immediately thought. It does take some running in and can be a bit tight for the first 1000 miles or so and certainly gets better/smoother with more miles on the clock.

Break in as a very reserved 40mph for the first 300 miles, which for most people just hasn’t been realistic. But with no reports of engine failures – apart from one I read of that failed on a trip back from India to Europe as part of a 13 strong group of Himalayans – it looks like the engine is built to take some abuse, with plenty of people already looking at how they might extract more power from it. It’s a fine line though. The engine suits the bike; its handling and its brakes. A few more bhp might be nice, but I don’t personally think it’s a priority to gain more BHP, and if you go down the path of upping the power it’ll probably never end. I think you just have to accept it for what it is and for some people it simply won’t be enough, and that’s fine.

I’ve found that the bike will cruise mostly at around 70mph, even with luggage, topping out at around 83mph. On some of the inclines in America, especially into a headwind, speed was sometimes down to around 60mph in fourth gear, and even on the flat it would certainly struggle to keep pace with the fast moving traffic on the interstate. For cruising pace it was about equal to a Kawasaki KLR650 that was also part of the group; that bike clearly more powerful but at cruising speeds suffered a certain amount of vibrations. Against some of the other bikes on the trip, such as the Suzuki V-Strom 650, Kawasaki Versys 650 and Honda CB500X the Himalayan was underpowered on the road and couldn’t keep the same pace of those road-biased bikes. Where the Himalayan did seem more favourable was on the dirt or rougher back roads, where the Himalayan’s supple suspension and more dirt-friendly riding position, not to mention the 21-inch front wheel, came into their own.

HANDLING

The bike handles much better than I was expecting. It has very conventional non adjustable front forks, with just a six-step adjuster on the rear mono shock. It shouldn’t handle that great. Most budget bikes don’t. But the tuning of the suspension for me is superb and what sets the Himalayan apart. It manages that fine art of being soft and supple for when the road is rough, but at the same sharp and composed enough to allow you to throw into the corners and really have fun on the bike, both off-road and on. It’s a spread of talent that I’ve only really experienced on my BMW R1200GS that had electronic suspension that you could adjust on the move for road or off-road situations. That the Himalayan manages both environments without any trick electronics is a testament to the guys who set it up. For me then, the suspension (and chassis) is probably the best element of the bike, with it the guys at Harris Performance in the UK (now owned by Royal Enfield) largely responsible for that element of the bike. They’ve certainly done a cracking job.

On the road there’s minimal pitch into corners. The bike corners flat, and even with the 21-inch front wheel is nimble; agile even. Tyres by Pirelli are the dual sport MT60s, which offer excellent grip and I’ve never found them wanting when pushing on. I’ve tried the bike with knobbly Mitas E09 and even with those the Himalayan still handled crisply on on the road. The bike surprises a few people, especially when a lack of power is compensated by the carrying of momentum that the well set up chassis and suspension allows. It’s actually a very easy bike to ride fast in the corners, the only compromise being the relative lack of ground clearance and soft suspension that causes the centre stand to drag if you start pushing on, especially with the bike fully loaded. I see the compromise in the ground clearance a result of the bike being designed to have a low seat height (800mm), which in many cases is more important than ground clearance, especially for shorter or more novice riders.

Off-road the bike again really impressed me. I do a lot of trail riding and very few bikes feel ‘right’ out of the box. I like the natural standing position. The bars and pegs are well placed for me at 5’10”. I don’t need bar risers and I wouldn’t bother with wider bars. I like that the footpegs have a nice serrated pad with an easy to remove rubber insert. I like that whilst on paper the bike weighs 191 kilos it doesn’t feel anywhere close to that in the flesh. It feels well balanced, agile, manoeuvrable, and above all else easy to ride on the trails, especially with that low seat height. What helps the bike along on the trails is the engine. It’s gentle revving nature means that it finds a lot of natural traction, and even on relatively road-biased tyres it can still find good grip and speed. It has a nice ‘chug’ factor as well, meaning that you can leave it second gear and it’ll pull along at low speeds without a lot of clutch work to stop it from stalling. It makes it very easy for the novice rider to ride.

People say why not just buy a Tenere 660 or a KLR650, which indeed are two both great bikes, but the difference is that those bikes need a strong or confident hand to be ridden effectively in the dirt. They can be heavy and cumbersome if you’re not sure what you’re doing and they can easily get you into trouble given their seat height. The Himalayan on the other hand is less intimidating and therefore more encouraging of you to get out and explore on it, and to me that’s a big thing in its favour. Those other two machines are no longer available to buy new, and for me there’s a huge appeal in buying a brand new bike that doesn’t have the bodges or fixes of a second hand bike. Having a two year warranty is also a big appeal for someone who isn’t hugely mechanically minded.

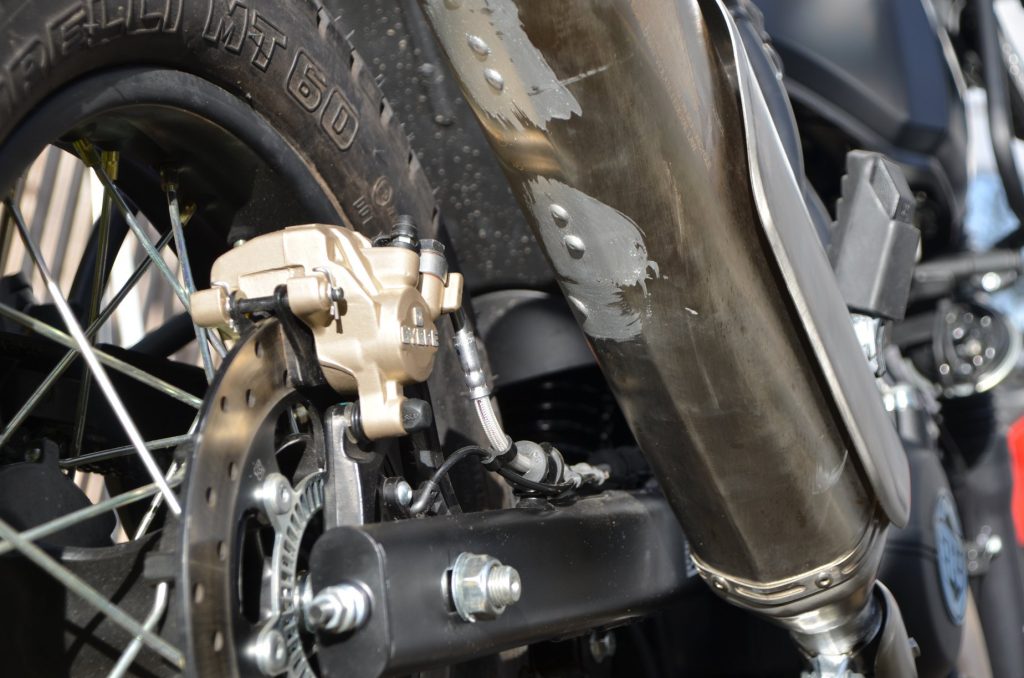

BRAKES

The brakes have come in for some criticism from some quarters and it’s easy to see why. The single disc front brake by ByBre (Brembos Indian subsidiary) lacks bite and when you go to grab it it feels like there’s nothing much there. There is something there, you just have to use a couple of fingers and give it a good squeeze, which is something we’re not used to on modern bikes. People have experimented with uprated pads with mixed feedback. To me, the brakes suit the bike, in that they’re soft and gently engaging and aren’t going to catch you out, especially off-road or on loose gravel where I don’t really want an aggressive front end bite. The Himalayan does have ABS which sadly you can’t turn off. Some have pulled the fuse, others have wired in their own switches. It’s not an issue for most of the time, just when you start pushing on off-road and the presence of ABS isn’t always appreciated. The BMW G310GS and CRF250 Rally both have switches to disengage their ABS systems, but only on the rear wheels, not front.

The back brake of the Himalayan is much sharper than the front and does bite immediately. I find on the road that combining back brake with front brake gives decent overall stopping power. Pad wear has so far been acceptable, with it still running the original front pads but having switched out the rear pads at around 10,000 miles, more as a precaution than a necessity as the bike was being readied for the America trip and the pads were looking a little low. The brake hoses are braided as standard, so there’s no gain in braking to be found there.

LUGGAGE

To me this is where the Himalayan really stands out and makes it a great travel bike. It’s not only that you can purchase official Royal Enfield aluminium panniers for £500 that are easy to bolt on and fit nicely inside the mirror width, but also that the front rack is so useable for strapping additional dry bags or fuel canisters to. Not only does this give you more place to strap the kind of gear I need when leading a tour (first aid kit, spare waterproofs etc) but also by mounting some of the weight at the front of the bike it helps keep the bike better balanced, preventing it from running rear end heavy, which is often the case with a fully laden adventure bike. I’ve been using a couple of Alt-Rider 14-litre synch bags that strap neatly to the racks, although others have found good options at the army surplus store for not a lot of money.

The bike also comes with a rear rack as standard which isn’t so handy given how small it is. It’s also quite weak and only rated to carry four kilos or so. Some riders who have mounted top boxes have found it snapping, requiring either reinforcement plates welding in, or the fitment of an uprated rack that UK firm Hitchcocks now offer. Rather than use the rear rack, I’ve found that a 40-litre dry bag fits perfectly across the pillion seat, which itself sits perfectly level with the top of the panniers to give a nice flat platform on which to strap things. There are also plenty of hooking points for straps and bungees, which makes attaching luggage that bit easier than on some bikes.

The standard fit aluminium boxes have also been a good purchase. So far they’ve proven themselves waterproof and feel as sturdy as the main brands in the pannier business. Their origins are thought to be a Chinese brand, re-badged and sold as Royal Enfield panniers, but irrespective of who makes them, they’ve been ideal for the trips I’ve used the bike for. At 24-litres each they’re not a huge pannier, but all in all they’re a good product for the price and seem to be able to withstand moderate abuse.

Another option is soft luggage, with Enfield dealer Cooperb in Northampton selling their own soft luggage racks as well as the Kriega bags to go on them. Cheaper options come from Army surplus store or the likes of Lomo who have a pair of waterproof dry bags for £50. The Himalayan is versatile to load up with luggage and for me that’s been a big appeal. For trips of longer distance others have fitted plastic fuel cells to the front racks, whilst the 15-litre metal tank is perfectly suited to take either magnetic or strapped tank bags.

SERVICING

Service intervals are every 3000 miles for valve check, and every 6000 miles for oil and filter. This seems a bit out of kilter and it’s one of those headline figures that has given people something to sniff at. The 3000 mile valve checks aren’t ideal, especially if you’re wanting to maintain your two year manufacturer warranty. I’ve found they don’t always need adjustment and for an average DIY mechanic it’s something that you can do or learn to do yourself. They’re a simple screw and locknut design so a set of feeler gauges and a bit of patience and you’re done. Oil and filters are also simple to change and fundamentally, given that it’s a single cylinder air-cooled engine with minimal electronic intrusion, it’s a simple bike to work on.

Prices have been around £140 for the main service, with some other riders reporting of getting it cheaper at their local dealer. The 3000 mile interim valve check service is closer to £70, although I tend to get the full service done each time as new oil and filter won’t do it any harm every 3000 miles.

To compare it to its peers, the BMW G310GS requires servicing every 6000 miles with valve check at 12,000. The Honda CRF250 bikes are every 8,000 miles with valve check at 16,000, whilst Suzuki V-Strom 250 and Kawasaki Versys-X 300 both have interim 3000 mile service intervals like the Himalayan as well, with costs for the main services much higher than that of the Himalayan. The Enfield is therefore not alone in requiring frequent servicing, but so far I’ve not found any reason why it shouldn’t be beyond the efforts of the average DIY mechanic. Fuel economy for those interested is consistently above 70mpg, and closer to 90mpg on back road runs. This gives a possible range of 250 miles from the 15-litre tank.

The bike comes with a relatively substantial tool kit under the seat. You have everything you need to remove the wheels and panels, although there’s no C-spanner for rear preload adjustment. I like that the front and rear axle bolts are the same size, therefore taking the same tool. It’s also a big help that the bike comes with a centre-stand as standard, making the bike easy to work on. To get to the valves involves removing the two bolts that hold the tank on, disconnecting the fuel line and fuel level sensor and from that the intake and exhaust valves are easy to access. The inlet valve gap is 0.08-0.10 and the exhaust gap 0.23-0.25. Some owners have experienced cold (and hot) stalling issues, with it commonly discovered to be a pinched breather pipe that just needs re-routing.

FAULTS SO FAR

The faults on mine have been minimal, and bearing in mind that it’s had some hard use over the year. The main thing it needed was steering head bearings being re-greased at the 4100 mile service. There’s been a few cases of them drying out or suffering water ingress from the storm flap at the bottom of the headstock that is insufficient against heavy rain or jet washing. It was a simple case of dropping the bearings and re-greasing them. Not a big job at the dealer.

In the last few thousand miles I’ve had a bit of ‘clack’ at pick up off the throttle, with the dealer replacing the cam chain tensioner, which partially quietened it, but not completely. From the forums, owners report a variety of engine noises and things they can hear, but I think with a relatively big single cylinder air-cooled engine you’re going to get some mechanical noise and I find ear plugs to be the best solution for that. In terms of noise, the standard exhaust gives a nice deep tone, with little gain to be made from the aftermarket Lextech end can that I tried.

One criticism of the bike is the side stand that is a touch too long and therefore the bike stands a little too upright. A few times the bike has gone over as a result, especially with the suspension compressed when fully laden. A solution would be to chop a bit out of the side stand, others have ground down the lug on the pivot to allow the stand to rotate forward that little bit more, thus increasing the lean angle of the bike when on the stand. It’s not a bit issue, but something to be mindful of.

The seat on a long run can also cause discomfort. It uses a soft foam and over a few hours its compression means that you can just begin to feel its base plate pressing into your thighs. I was given a Cool Cover to try, a sort of plastic weave slip on cover designed to increase ventilation to your backside, a side benefit being that it gives the original seat more rigidity and therefore reduces its compression. With the Cool Cover on I can do as many hours in the saddle as I need, riding a couple of 650 mile days in the time that I’ve owned the bike. They’re not cheap at £65 but they have done the job. Another option would be a lambs wool seat cover.

CONCLUSION

After almost 16000 miles on a bike that I’ve bought and paid for myself (it’s not a press bike) I have to say that I think the Himalayan is something of a revolutionary bike, simply because it serves as a great reminder that a company can build a simple yet effective machine and not charge the earth for it. That it comes with everything you need as standard, be in the centre stand, front rack or rear rack, means that it can be ‘adventure-ready’ for less than what other manufacturers in this sector are charging for a base level bike.

For me it’s also a much better bike than its price tag suggests, from its suspension to its handling and to way its stood up to serious abuse. It feels like a bike that was designed from the ground up with a clear idea of what it wants to be and what it wants to offer the rider. It’s ironic in that in being designed for the domestic Indian market it also translates perfectly to what a long distance rider in the western world might want and in that regard it seems like a bike that no other manufacturer could have designed or built. The Honda CRF250 range are great bikes but I can’t help but feel that Honda were capable of better things and the new 450L doesn’t seem entirely suitable as a travel bike (and it’s two and half times the cost of the Himalayan)

The Suzuki V-Strom 250 is likeable but essentially a road bike given adventure styling, whilst the G310GS by BMW leans a lot on the badge rather than on its credentials as a bike. I can’t help but feel that BMW were capable of making something much more than that bike, as evidenced by the huge improvements the Rally Raid upgrade kit makes to it. That we’re even comparing a Royal Enfield in the same sentence as a BMW shows just how far the Indian brand has come, and I think for me that’s what I like about it; the Himalayan feels like a bike built by a company on the rise, as good as they could make it, with the upcoming 650 twins likely to take that rise even further. Conversely, the G310GS feels like a bike built by a company trying to squeeze as much profit out of the GS badge as possible, with the bike maybe not quite as resolved as a travel/adventure bike as it could be. Having said that, owners of that bike seem very happy with their purchase so perhaps the Himalayan and the 310GS are just two different bikes for two different types of rider, and that’s fine.

In summary, were I to go around the world tomorrow and I could choose any bike on the market today I’d stick with the Himalayan. I like the way it rides, I like the way it looks, I like the way it makes you feel. I also like the simplicity of the design and the ease of which it is to work on. I like that it covers ground on the road with no real problem, whilst at the same time having the capability to take you off the Tarmac without any great level of intimidation. You can explore on it. You can get lost on it, and you don’t ever feel like it’s going to get you into trouble, or that you’re not going to be able to man-handle it if things go wrong. It is then the perfect blend of old and new, and obviously it’s not going to be for everyone and for some people it’s going to be too slow and not exciting enough on the road, but if it suits your type of riding and the purpose of what you need a bike like this for then I don’t think you can really go far wrong. Nearly new ones are on the market for as little as £3300. For such a relatively little amount of money you can have a bike capable of so much. And in this day and age, that’s just unique.

VIDEO REVIEW

Excellent write up!!

I thoroughly enjoyed it… And. Totally want a new bike 😉

Thank you

Big up !

Thanks a lot for your fine analysis of our bike on and off road.

Fred

Great review Nathan. And I must agree that for the money it’s every thing the Adventure market should be pushing.

Cheap, easy to work on, Carrys plenty of luggage, big tank, and I’m sure would get you around the world with money still in your pocket.

Great write-up, a few friends rode these in India via the Royal Enfield tours and we’re quite impressed. Your report supports their desire to get one. I would love to ride the TAT on one of these!

Excellent Review by Nathan.

Incredible detail and full analysis

Far far better than magazine journalists as Real World detail not high expense account jollies.

Thanks for this extensive review – very helpful and insightful. I’m contemplating one and the fact its simple and adventure ready sounds quite nice.

Having owned my own Himalayan for about 6,000 miles so far I can confirm that Nathan has well and truly nailed it with this extensive review. The bike is such an honest, versatile workhorse that provides basic transport and fun. I said to a friend recently that I feel that in many ways motorcycle manufacturers have forgotten what a bike should be and, with the Himalayan, Royal Enfield have reminded them. I certainly never tire of riding mine!

How about night riding ? Is the headlight any good ? As over many years of riding different bikes this can be a disappointment not mentioned on road tests

Done about 14000 miles on mine 22000 km in india on the carbureted version no ABS

(These were the ones which everyone whined about) had no problems except the steering yoke bearings and the rear top box stand (rear rack) breaking. . . Twice

The bike is a sweet ride (would have loved some additional horse power) she grows on you and I for one am real happy to have her.

The 650 interceptor would complete the garage.

🙂